Biodiversity initiatives in cities, Helsinki, May 23rd 2024

Cities can contribute to biodiversity through land-use governance actions on ecosystem services in the natural and built environment. Biodiversity, on the other hand, brings benefits for cities through healthy and pleasant living environments in many ways.

In the opening presentation of the seminar, Katja Lähtinen, Research Professor, Natural Resources Institute Finland, brought up cities’ role in fostering local actions and promoting the UN Sustainable Development Goals on environmental, social and economic sustainability.

Marc Metzger, Professor of Environment and Society, The University of Edinburgh (UEDIN), introduced CircHive’s work with cities and welcomed CircHive’s case-study cities to present the local initiatives to support biodiversity in their cities:

The presentations of CircHive’s case-study cities were followed by examples from Finland: the City of Helsinki and the City of Tampere:

Biodiversity footprint of the City of Tampere, Sami El Geneidy, Doctoral Researcher, Biodiversity Footprint Team Lead, University of Jyväskylä

After the presentations, the seminar participants were divided into three small thematic groups: 1) Land use goals; 2) Collaboration with different local actors; 3) Citizen science.

Land use goals

The themes raised during the discussion regarding biodiversity in cities addressed actor roles and power, timescales of decision-making processes and outcomes concerning the land-use management actions in cities. In all, it was concluded that fulfilment of biodiversity aims in cities is an outcome of consensus between long-term strategic goals and short-term practices for biodiversity that both are affected by local policies and governance structures.

To increase biodiversity in cities, clear division of power and common understanding of goals and actions between local politicians and civil servants is needed. In addition, as a conceptual approach for biodiversity in cities, it was mentioned that the quality of biodiversity may be “good” or “bad” (e.g., richness in the number of species is caused by invasive species). This should be remembered in all discussions on cities’ biodiversity actions.

Collaboration with different local actors

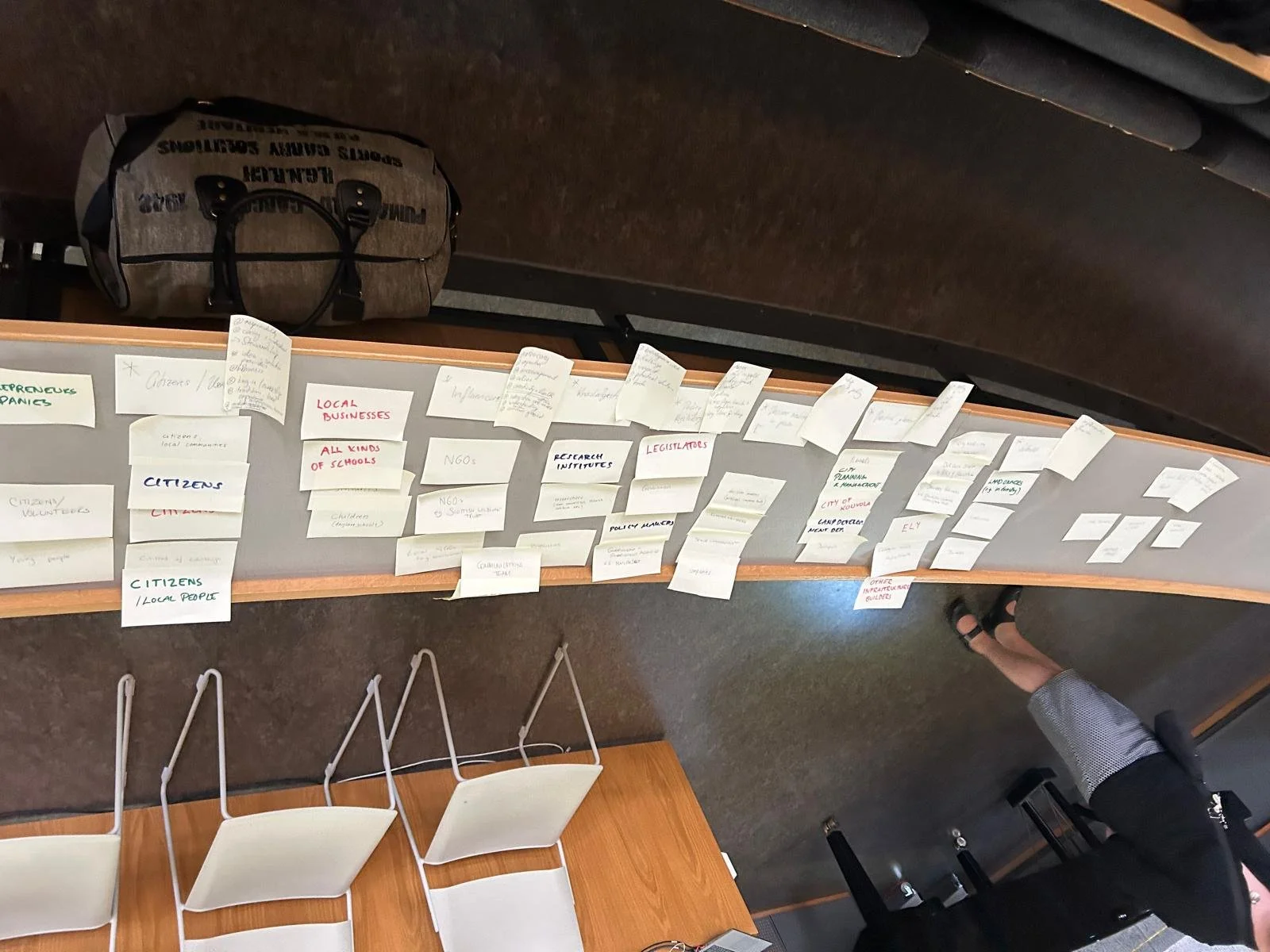

The group discussion illustrated a decision-making landscape which is inherently collaborative and multifaceted. Action for urban biodiversity requires concerted efforts of citizens, policymakers, planners, businesses, researchers, NGOs, landowners, educators, media professionals, city staff, infrastructure builders, and government agencies. Engaging these groups at an early stage of developing action ensures that the initiatives are grounded in the realities of local context and a sense of ownership and responsibility can be built towards protecting biodiversity. Interaction with various groups inevitably brings challenges and potentially conflicting interests. One-to-one meetings, collaborative planning, engagement of diverse stakeholder groups and an evidence base for the impacts of activities are part of the toolbox used by city administrations promoting biodiversity.

The group revealed interesting perspectives on how discussions in stakeholder interaction could take a wider radar on the changes ongoing. For example: How do we involve the future generations in planning biodiversity in cities? How can different time horizons be discussed, and overall, how do nature and changes in nature affect cities? Do other species than humans have agency for biodiversity in cities?

Citizen learning and Citizen science

The group discussed diverse experiences in engaging citizens to support biodiversity data collection and research. Examples included asking the public to help locate the rare species to speed up fieldwork, understanding citizens’ spatial preferences through participatory GIS, and galvanising citizen support to eradicate invasive species. It was clear that objectives and citizen engagement methods need to be carefully aligned, citizen motivation needs to be understood, and rewards may be required to encourage participation. A first requirement is to be absolutely clear about the project objective and then whether citizen science is the most effective approach. There was general agreement that citizen science projects require carefully considered design and appropriate resourcing.

Some groups took a relaxed approach…

…while others were working very hard!